I struggled with The Necessary Stage's Gitanjali when I reviewed it in 2014. It was a sweeping but disparate production, each element straining in a different direction in an attempt to grasp or portray something cosmic and transcendental. Who, or what, did Tagore symbolise? How did his poetry fit into the story of a family struggling with carrying on the tradition of Indian classical dance? And what of his muse, Kadambari? The attempt to bring multiple disciplines together - dance, multimedia, theatre, a lush soundscape of the experimental and the classical - felt rough at the seams.

Ghost Writer isn't quite a reworking of Gitanjali as it is a reincarnation – the same but different, echoes and excavated memories of a past life given an entirely new body. It's a pared-down, intimate 75 minutes in a black box that manages to articulate a great deal more than its former, unwieldier incarnation. I'm not sure if those who haven't seen Gitanjali might find Ghost Writer baffling or liberating (to quote a friend with whom I discussed the show after), but as someone familiar with Gitanjali's characters, I found aspects of their personality already shaded into my mind and now given flesh.

Ghost Writer is, in a sense, about ghosts. It is about how one generation of a family haunts the next, but also about how an artist's inspiration and muse can turn into a spectre that haunts her every sentence or dance move. Tagore is haunted by Kadambari, his sister-in-law, who died tragically. Star bharatanatyam teacher Savitri (Sukania Venugopal) haunts her protege, Priya (Ruby Jayaseelan), as the younger woman moves to Canada to pursue new forms of dance, but ends up exotifying herself, "becoming more Indian than India", to become a prominent choreographer. But Priya haunts Savitri, too, even in her absence, as Savitri struggles to find a successor to lead her dance institution. Savitri's son, Shankara (Ebi Shankara), is haunted by his mother's inspiration, Tagore, so much so that he devotes his PhD to the study of the writer. And Shankara's wife, Nandini (Sharda Harrison), is haunted by the death of her sister - and the parallels between that death and the death of Kadambari. Who dictates the life we choose to lead? Do we choose our own path, or do others nudge us onto it? Is the dance a divine one, or is it the artist's own?

The production starts out slowly, with a few clunky exchanges, but it is the second half that brings the play home. The character of Jeremy (Jereh Leong), the Canadian dancer whom Priya finds alluring, feels significantly shallower than the rest, an arc I honestly felt could have been done away with or played as a non-speaking role. (Correlation: He's not in the stronger second half.) Once the play is done laying out its exposition, it mines the complex relationships that orbit each character, and that is the richest part of the performance.

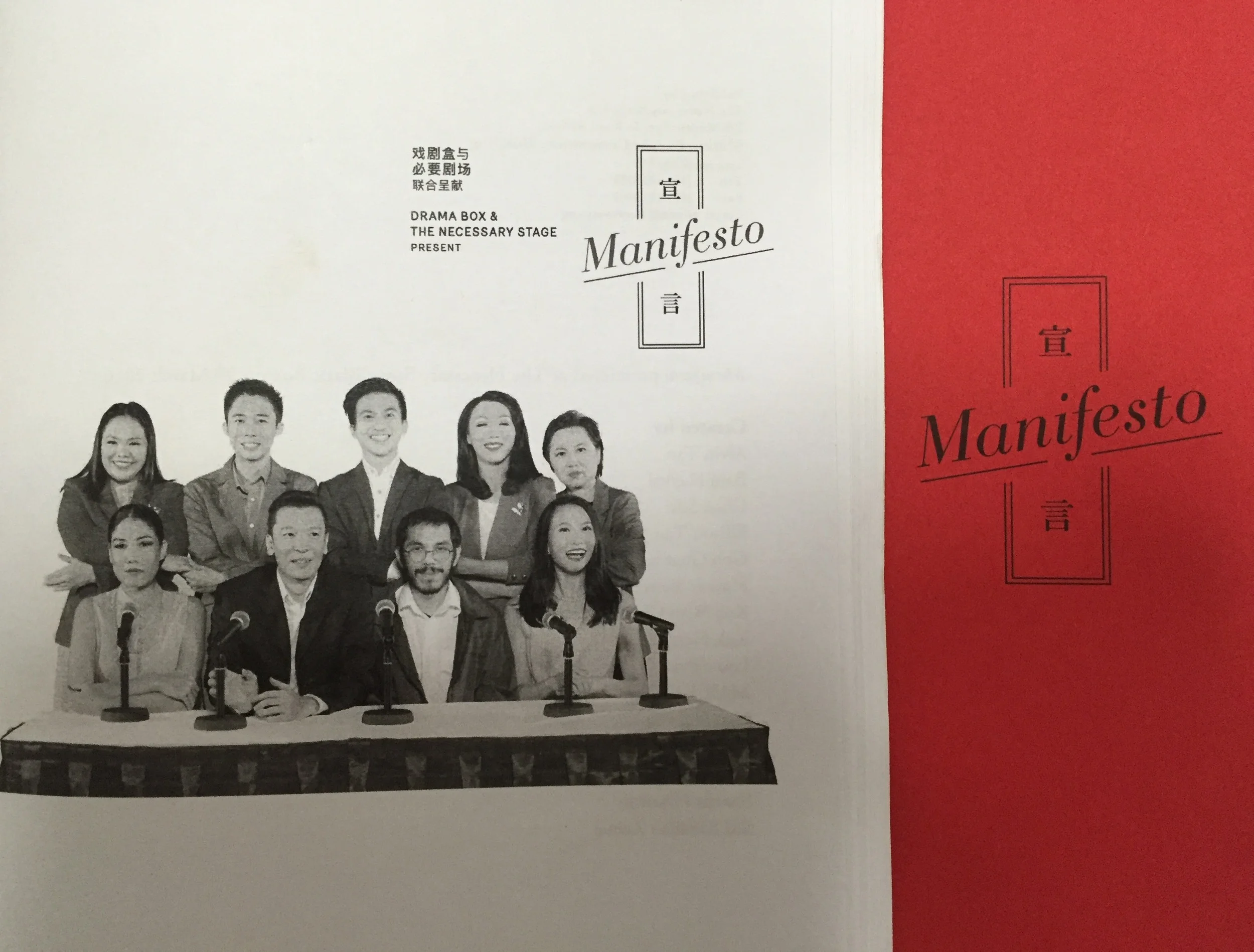

I think Ghost Writer continues the journey The Necessary Stage has taken, in this chapter of their output, into what a truly collaborative, interdisciplinary production looks like, giving a creative team from all backgrounds equal voices throughout rehearsal and development, and giving a prominent platform to typically 'design' elements (multimedia, sound, spatial design). From Gitanjali (2014) to untitled women (2015) to Manifesto (2016). It brings out some surprising and intriguing results. What I appreciated much more fully in Ghost Writer was its strides to make the production truly multidisciplinary, where a conversation could be begun in speech but concluded in dance and still have its narrative arc remain completely clear. Actresses Sukania Venugopal as the stubborn Savitri and Ruby Jayaseelan as her star pupil Priya are twin revelations in this aspect and throughout the production. Their opening conversation, from Priya's growing success in the school to her sudden departure, is exquisitely portrayed through Indian classical dance, particularly in that single, pivotal moment where Savitri realises that her student has, she believes, betrayed her.

While dance blends marvellously into the mix, the multimedia element of the production is less consistent. Some of the visuals are stunning to behold, particularly in a scene where Priya, reflected in a mirror and projected on several screens through some clever camera work and choreography (I'm still bending my head over how they pulled that off), dances a solo that is at once vulnerable and powerful. But some of the video work over-informs, the way a melodrama might overdo its nudge-wink when the audience already understands a plot point. I get the sense that the creative team is playing with that tension between film and stage here, the same way that Ghost Writer's multimedia artist Brian Gothong Tan explored that tension in 2012's Decimal Points 4.44, where he challenged an audience to watch both film and theatrical versions of a story simultaneously. That works if both elements are equally strong. Here, some of the film feels redundant, e.g. a short that lingers over Priya and Jeremy's intimate relationship (and then he recedes into the background for the rest of the show, so I don't understand any of his influence over her), or another that portrays what happened to Nandini's sister (the beauty, I felt, was in the agony of the mystery - the way we will never know why Kadambari killed herself).

But Ghost Writer, unlike the ambivalence I felt after Gitanjali, emphasises redemption. Nandini's storyline comes to the fore as the production unfolds. She starts out a lonely and bereaved 'expat wife' in an arranged marriage, not unlike Kadambari, but then finds her voice in writing. She creates her own agency (and by agency I mean her capacity to act of her own free will). The characters of Ghost Writer exorcise their ghosts not through violence or defiance, but through letting go. I think Tagore's beautiful poem, revealed close to the end, embodies it best:

THE FIRST GREAT SORROW

I was walking along a path over-grown with grass, when suddenly I heard from some one behind, “See if you know me?”

I turned round and looked at her and said, “I cannot remember your name.”

She said, “I am that first great Sorrow whom you met when you were young.”

Her eyes looked like a morning whose dew is still in the air.

I stood silent for some time till I said, “Have you lost all the great burden of your tears?”

She smiled and said nothing. I felt that her tears had had time to learn the language of smiles.

“Once you said,” she whispered, “that you would cherish your grief for ever.”

I blushed and said, “Yes, but years have passed and I forget.”

Then I took her hand in mine and said, “But you have changed.”

“What was sorrow once has now become peace,” she said.

Stray thoughts:

- I realise I didn't mention the fantastic sound artist Bani Haykal and vocalist Namita Mehta, the sonic backbone on which the piece hinges. They are the rhythm to the narrative, carrying the push and pull, the dramatic tension of the plot. Bani won the 2015 Life Theatre Award for Sound Design for his work on Gitanjali.

- French-Laotian dancer and choreographer Ole Khamchanla drifts through the production as a sort of representation of Tagore. The piece concludes with what feels like a dance-meditation on what it means to be a part of this path of life, a hypnotic, entrancing epilogue that compelled me to sway, in my seat, to the beat.