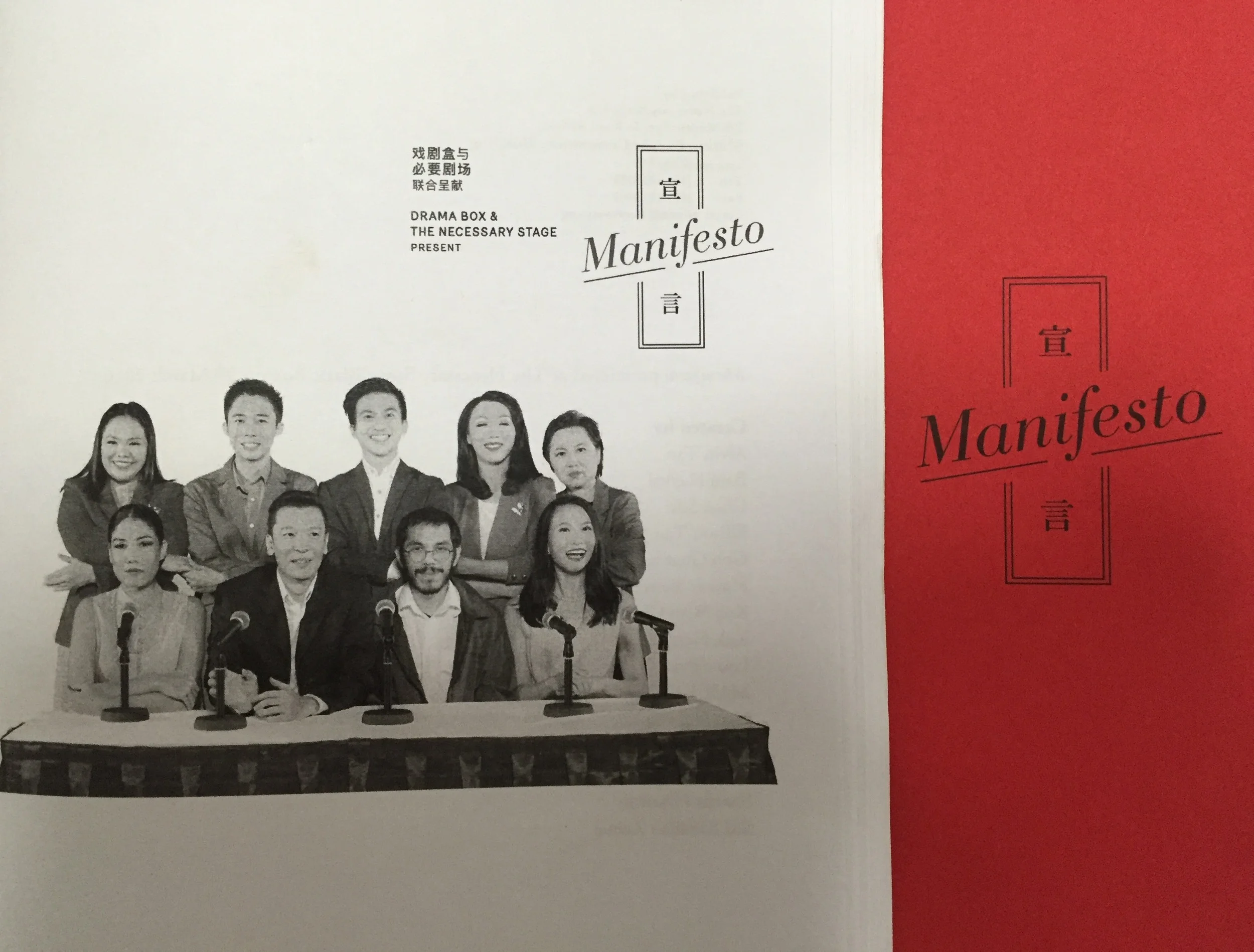

Three years ago, I attended a press conference on the top floor of Drama Box's narrow shophouse premises in Chinatown. A group of arts practitioners had come together to unveil their Manifesto For The Arts (page here), what they hoped would be a call, a rallying cry, that artists and arts lovers would be able to align themselves with. I was a younger reporter at the time, only just beginning to understand my beat, and the sound of a 'manifesto' was at once empowering and intimidating to me.

This was their manifesto:

- Do not attempt to define Art for others.

- Art is fundamental.

- Art unifies and divides.

- Art is about possibilities.

- Art can be challenged but not censored.

- Art is political.

I wrote about it in the paper, as did several other journalists, but as time went on and other arts policy issues came to the fore – censorship, term licensing, grants structures, changes of leadership at the various ministries and statutory boards – the sound of that rallying cry got fainter. Until The Necessary Stage (TNS) and Drama Box announced that they would be doing a collaborative production titled Manifesto.

Manifesto, I have come to realise, is all of the above.

- It does not attempt to define itself. When TNS and Drama Box said that this would be a 'challenging' play, they were putting it lightly. It ignores genre and convention. It is an epic but also a series of vignettes. It blends film with 'liveness' and more static audio and visual installations. It is a meta-play – you see the actors preparing to enter the stage, their costume changes, the actors playing an actor playing another actor, it presents a genre of theatre (e.g. forum theatre) within another genre of theatre (e.g. naturalism). Actors and designers – who would often take a more behind-the-scenes role in a production, such as the sound designer or the multimedia designer – were all on an equal, open footing, all visible on stage. All of them had speaking roles.

- It is fundamental. Manifesto depicts artists at their most elemental, creating work and examining why they create what they create, and how they respond to reactions to their work and who they are.

- It unifies and divides. There has been an outpouring of support and critical acclaim for the production, but there have also been some detractors.

- It is about possibilities. Or perhaps finding possibility in impossibility. Artists are hemmed in by cycles of history that seem to repeat themselves. One theatre group with a cause is spawned, only to struggle, collapse, and then birth another theatre group half a century later out of its ashes – but is it a birth or just a moment before death? Forum theatre – where audience members are allowed to stop a scene and replace any of the actors to see how they might resolve a conflict better – is used heavily as a device of possibility. How can these narratives, these tragic personal histories, be altered? What knowledge and foresight can we draw from counterfactual history?

- It can be challenged, but not censored. It was certainly challenged (see: 'Singapore play about role of artists gets R18 rating', The Straits Times; and Alfian's response to the rating), but we can debate whether it was subject to censorship or not. The play often depicts self-censorship as endemic of Singapore of the 1980s, where practitioners censor themselves by dropping key words at the end of each sentence, e.g.

BT: "We can all speak—"

Roslan: "All our plays have been—"

Sheila: "I can write anything I—" - It is political. Manifesto traces the struggles of a group of artists as they come up against the machinery of the state, be it detention or censorship. But it also looks at ideology, guiding principles and convictions, and purpose, and what it means to be not simply a political actor but a political being.

Manifesto was, in that sense, an artistic manifestation of the set of principles that a group of artists in Singapore had set out to be united by. It is the sort of ambitious, unflinching, chaotic and confrontational art that artists here have struggled, for decades on end, to defend.

The linear timeline in Manifesto is often interrupted and most of the actors play multiple roles and speak a hodgepodge of several languages (English, Chinese, Malay, Hokkien), which might take some time to get a firm handle on (the disorientation is very deliberate and the production does not hand-hold the inexperienced theatregoer).

But in a nutshell, a group of artist-activists come together in 1956, during the tumultuous development of a national identity in pre-independence Singapore. Their establishment of a company lays the path for another group of artist-activists in 1986, who are swept up in the McCarthyistic Marxist arrests of the late 1980s. In the present day, 2015-2016, artists try to make sense of the industry's dark history and grapple with the ghosts of their past, while in the future, 2024, questions of artistic and political succession in Singapore (Who will be the next MP? Who will be the next artistic director?) come to the fore, placed on equal footing. The characters are sometimes very thinly sketched out, with a few feeling less like people and more like devices to move the narrative forward and throw some dramatic tension into the mix, but the actors do an absolutely stunning job within the confines of their short sketches to flesh out as much as they can of their talking heads, particularly the characters who are composites of real-life artists and detainees.

But, dare I say it, I don't think Manifesto will be remembered for its lack of characterisation, but for what it managed to condense and portray in a very short period of time.

Manifesto draws from TNS and Drama Box's previous work: they were pioneering groups in promoting forum theatre in Singapore, and detention without trial and political choice are large themes in productions such as Gemuk Girls (2008) and Model Citizens (2010). But I think this marks the first time that they have turned their focus so strongly to the Singaporean creator of art. This self-reflexivity ties in with a tide of artwork that has also put the Singapore artist in the spotlight – some in more powerful ways than others – such as Sonny Liew's graphic novel The Art Of Charlie Chan Hock Chye (2015), which reimagines what Singapore might have been like if Lim Chin Siong had taken the reins instead of Lee Kuan Yew; Toy Factory Production's Upstage (2015), a measured, careful tribute to the origins of Singapore's Chinese-language theatre; or (to a, well, much less effective extent) Nanyang – The Musical (2015), which looked at the lives of the Nanyang-style painters in Singapore in the 1930s-50s. Then there has also been a swell of productions that look at alternative histories and narratives that don't completely align with the 'official narrative' that the Singapore authorities are fond of using as the definitive Singapore history. That official narrative is a valid take on the country's past – as are many of other narratives, told from different perspectives. Teater Ekamatra's Geng Rebut Cabinet (GRC; 2015) and Wild Rice's Hotel (2015), as well as Tan Pin Pin's documentary about political exiles To Singapore, With Love (2013) are some instances of productions that interrogate the political narratives that are often taken as fact, rather than a matter of perspective.

Taken together, Manifesto fits in well with this movement of artwork that seeks to overturn historical and cultural amnesia in Singapore. And if not to overturn, perhaps to introduce a few cracks in the armour. It is very bald, and very ballsy, about its agenda to expose the inordinate struggles of art-making in Singapore, and its manifesto for the arts is in full, showy, obvious view. This, as opposed to the opacity of the state's manifesto, e.g. it promotes a certain brand of art, but not others, without explaining why. (Case in point: The MDA's R18 rating of Manifesto for 'mature content', with very little elaboration.) I don't think it proclaims that artists should get away with murder, but that the role of the artist is to provoke, to confront, to challenge, to delight, and to dismay, that the artist is as equally prone to bouts of debilitating humanity as the rest of us: spying on and betraying their peers, hands tied by bureaucracy, self-censoring, sometimes incredibly entitled and bratty.

Manifesto ends on an ambivalent, ambiguous note. A stage/production manager and an actress-director shake hands, having decided that they will start their own theatre company with their own manifesto to abide by. Yes, we all think, this is it. This is the moment where the cycle begins anew and they can strike out on their own, and make a difference.

Or is it? Will the cycle just continue as it has before? Do artists hold on to their manifesto, or simply fall in line behind the state's unspoken manifesto? Will art ever matter – and matter enough – in Singapore? Have we already lost the war, with a public that is largely more concerned with what they view as more important, bread-and-butter issues? Does Manifesto only preach to the converted (the artists, the artsgoers, the arts community), and with its brief run in a tiny black box space, will it ever send ripples far enough to ever make an impact?

I don't have the answers to these questions. But I was thinking about the communality of Singapore theatre in the 1960s, captured in Dr Quah Sy Ren's authoritative book in Chinese-language theatre in Singapore, as well as in Upstage, where groups and individuals would come together on a regular basis, break bread with each other, and work collectively to create art. It is this coming together that Manifesto pieces together from the ashes of friendships and working relationships torn apart by detention and betrayal. The act of creating Manifesto itself was the result of two groups with overlapping histories coming back together. I think it is this arts community that we must come together to nurture, to heal, and protect. That is our manifesto.

UPDATE:

Stray thoughts about the performers and the use of multimedia:

- So many clever touches from the use of film as both documentary and mockumentary, courtesy of a lot of great experimentation from Loo Zihan. I liked how the present-day performance artist Rumiko uses an iPhone the way one might use Snapchat or Periscope today, to do a 'live' feed on arts events. And of course the 'documentary' snippets that recreate the confessions done on public TV during the 1980s that were breathtakingly authentic.

- There's a scene that actress Goh Guat Kian does as her character Siok Dee towards the end of the play, captured on film, that was quite gutting and that I found out later she had improvised, i.e. her improvisation done in rehearsal made the cut into the final film with next to no changes. Guat Kian, you are incredible.

- Also cried buckets during a scene where the inimitable Siti Khalijah, as the long-suffering actress Som, waiting for her husband to come home, ages through the decades. I know I wasn't the only one.

- I have a soft spot for forum theatre, and it was very pleasing to see it used as a practical, matter-of-fact way of resolving conflict and trouble-shooting. Kind of a small reclamation of the 10 years where funding to forum theatre was proscribed here.

- "Art is the end of the reviewer." Well, that's really—